Defining a New Vocabulary for Voice Characterization

In the world of international voice dubbing, Jacques Barreau sees the need for a universal vocabulary that will help actors properly place their voices and attain the perfect voice that is needed for a job.

I have spent the last five years travelling all over the world for Warner Bros. As a creative executive responsible for the casting of all of our animated product worldwide, I have the great privilege and opportunity to work with a wide variety of actors of all nationalities.

Of course, this has not always been an easy ride and I've had a few surprises. I remember one amazing mix session for Space Jam in Beijing, where I learned that the concepts of time and space are quite different in the West and the Far East -- it was the fastest mix for the world's biggest audience. Then there was the recording session in Bangkok, where I had to change the voice director because he couldn't ask the actors to redo a line. He was younger and owed respect to the older actors!

Besides the humorous stories, I realized very soon that I needed to bring some sense of organization and common references to the dubbing world, if I wanted to succeed in my quest to protect the integrity of Warner Bros.' animated celebrities by maintaining the consistency among the many international language voices of these animated icons. The first observation I made during my travels was that all the artists were taking different approaches in trying to reach this goal. One would think that most actors use more or less the same techniques to work with their voices. This, in fact, is not the case; the actors' different approaches results in inconsistencies in character.

In this article, we will talk about the voice characterization (the art of creating a non-human voice) used in animation. What do actors from different countries do to re -create classic animated voices in their language and how can we help them to do this? Our role is to explain voice placement techniques to actors who do not have this training. To do so, we need a common vocabulary to describe these techniques. As I mentioned earlier, up until this point, there haven't been common references, but this new vocabulary will guarantee the same approaches to characterization worldwide, and consequently, the consistency of animated character voices.

A Void to Fill

First, we need to define the two essential parameters of voice characterization. They are the voice placement and the voice effect that can be created by working with the mouth, throat, etc.

- Voice placement indicates in which area the actor places his voice. Later, I'll discuss the different areas where the voice can be placed and all the sounds we obtain from those areas.

- The voice effect defines the way of working with the throat, nose and mouth, which will help in creating a great variety of sounds.

Let's consider for a second the voice as a musical instrument. Like with all musical instruments, you can play the same note (pitch) with different colors. If I hit the strings of my guitar softly or hard or if I place my right hand close to the bridge or far away, the same note will have different sounds, or different colors. It will be the sound of a guitar (the basic voice of an actor), but with different colors (same voice placed differently). Like any serious musician knows how to change the sound of his instrument, any serious actor should be able to work with his voice the same way. The main difference is that the voice placement techniques are still much more mysterious than the instrument techniques, which is probably because there is no vocabulary to define these techniques.

Voice characterization, unlike music, is a new art. Musicians and singers all over the world know how to do a vibrato and use more or less the same techniques to play a common repertoire. This makes sense. What doesn't make sense is that all the actors have the same repertoire but don't share or sometimes don't know the techniques to place their voice correctly, which is the basis of voice characterization.

The first thing to do for an actor is to place his voice in order to get as close as possible to the voice of the character he is dubbing. When the voice is in place, he will then be able to concentrate on the character's attitude. The VD's (voice director) work is to make sure the actor gets the right attitude and keeps his voice consistent during his performance. This is a very common problem with animated dubbing in almost every country. The actor's concentration goes back and forth between the right attitude and the right voice. It is very difficult, especially at the beginning of a series, to remember and control both at the same time. It is the responsibility of the VD to make sure the actor doesn't lose the desired voice. The VD must communicate the voice placement information to the actor. Another problem: the VD, most of the time, concentrates on the attitude or on the acting side and does not help the actors in the voice characterization. One can argue that this voice characterization is so personal an approach to the actor, that only he can understand what he does. Here is where I do not agree. We need to be able to describe the voices and to explain the placement techniques. The same way a musician or a singer is able to describe a sound of a flute or a sound of a trombone and an effect like the vibrato, we should be able to describe the voice placement of any animated voice. Only then, we will be able to guide the actors and more importantly, guide them all the same way, using the same descriptions and vocabulary. How can we describe Marvin's voice? How is it different from the Tazmanian Devil's voice, for example?

Now that we know about the voice placement concept and the necessity of a vocabulary, let's try to create this vocabulary. This will be of course my proposition and like all propositions, they may not be perfect but have at least the merit of starting the process.

Voice Placement Positions

I divided arbitrarily, and based on my experience, the head in six regions or areas, organized around two lines or axis, vertical and horizontal, with the throat as the center. The vertical axis will define the high throat and the low throat and by extension, the top of the head and the very low head or chest. The horizontal axis will define the rear throat and the front of the throat. From the center (normal voice of most of the actors) throat, we can move our voice into the six areas. These six areas will give the basics of all the different characterizations.

1. The high throat (Bugs, Daffy, Tweety, etc.)

Although Bugs' and Daffy's voices are different, they are placed in the same area: the high throat. The difference comes from the effect: a nasal quality for Bugs and a lisp for Daffy. I will refer from now on to "mask" instead of nasal, which can be often misinterpreted and creates a voice of a person who has a cold (stuffed nose). We obviously want to avoid having Bugs sound like he has a cold! We'll explain later these voice effects.

2. The low throat (Taz, Sam, etc.)

Another example of two voices placed identically with different effects. This placement is used in general for big and thick voices such as Taz and Sam. Taz is full and big in the low throat and Sam is compressed in the same area creating a thick gravel effect

3. Air in the voice

This effect is also used frequently to make actors sound older than their real age. The same way we whisper, we can mix this flow of air with our voice to sound like an older person. The more air you mix with your voice, the older you will sound. We also have to be careful as some actors naturally put air in their voice, especially when they are tired. Our role is then to recognize the problem and ask them to project their voice more to reduce the airflow.

We just introduced another important parameter, the projection.

4. Projection

This is very often confused with volume. In fact projection and volume are two different parameters of the sound of a voice. The projection can be compared to the acceleration of a car and the volume would be its speed. As we can see, the two things are very close but not quite the same. The projection will be the force with which the actor is sending his voice out of his mouth, at a low or high volume. To project more will give a voice a more dynamic and energetic attitude. At the opposite end of the spectrum, we'll ask an actor to project less to give a calmer or quieter attitude. The projection has a big influence on the attitude, as we can see.

5. Nasal quality, nose, mask area

This effect can only be used when the voice is placed in the high throat. The nose and the mask are placed on the same horizontal axis as the high throat. We'll make a distinction between nose and mask, which will help to dissipate a very common misunderstanding. We'll define the mask as the area where the sinuses are. The nose will be the extremity of the area. These two areas create different effects. The mask is known worldwide because of Bugs, but a lot of actors who cannot separate the two areas, place their voice completely in the nose, which makes them sound like they have a cold and stuffed nose. This also makes the voice muffled and missing clarity. From now on, we'll refer to "mask" for most characterization, unless "nose" is specified.

6. Lisp

Sylvester and Daffy made this effect famous. The lisp, like compression, can be thin or thick (subtle or more pronounced). I recommend the actor put the top of their tongue on the left side of their mouth between the lips. Maybe the fact that we are generally right sided makes this side easier for everybody. (The effect created with the tongue at the center of the lips is different.) Then they have to speak and direct their voice along the tongue. The projection and the amount of air will create different lisps. More projection and more air will create a thick lisp and less projection with a little bit of air will create a thin lisp. If we listen carefully, we'll notice that Sylvester's lisp is thicker than Daffy's.

7. Recording techniques

I like to consider recording techniques and the microphone as part of the effects. The microphone works like the human ear and everyone can discern the difference in the tone of voice between someone talking at a normal distance or very close to the ear. The voice sounds bigger, with more bass and is of course more present. The actor's position in front of the microphone can help in changing the voice. Placed close to the microphone, the voice will sound bigger, fuller and present. Further from the microphone, the voice will sound thinner but in some cases will get some ambiance of the recording room. This is an extreme example and the engineer has to be careful to not get room ambiance when it's not needed. A present voice can always be put in perspective with equalization and reverberation at the mix but the opposite is not true. The right position in front of the microphone will help the actor to get closer to his character.

Help to Perform

The voice placement technique can help us save some good actors from being rejected during casting. This was the case of Dick, a play actor in Copenhagen. At the beginning of the test, this actor was sure he couldn't do the character and was ready to leave. He didn't know how to place his voice and was very far from the voice of Eustice in Courage. His big voice made him think that the fragile older voice of Eustice was impossible to reach. I saw that he was very flexible and after making him compress his voice and raise his pitch, we were already much closer. At this point, and this is a classic example, he had a tendency to go too high in pitch, almost to falsetto, which made him lose his gravel. I had to tell him to keep his compressed voice placed in the high throat. He understood where his voice had to be placed and did a very good Eustice. It would have been a shame to loose such a good actor, only because he was not shown how to place his voice.

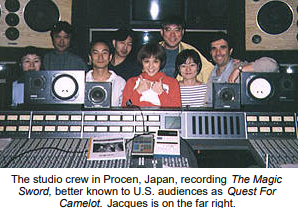

As we can imagine, all these placements and effects can be mixed to create an endless number of characterizations. The little variations in placement and the amount of effect will differentiate for example Sylvester and Daffy. The voice is placed in the same area but a bit lower in the throat with a bit of chest for Sylvester. The slightly different lisp is enough to make Sylvester and Daffy sound different and very recognizable. It is important to understand that these placements don't have clear borders. The voice can move from one area to the other with an infinite number of positions. The same way the different effects can be applied with in an infinite number of graduations. The combination of all the placements and all the effects makes characterization an art virtually without limits. Jacques is currently Sr. Creative Executive in the Dubbing Group at Warner Bros. He is in charge of worldwide casting of all animated Warner Bros. product and oversees the dubbing group's activities.

Jacques was awarded the gold medal in electro -acoustic music from the National Conservatory of Music in France, before becoming assistant professor in the Department of Music Sciences at the University of Provence. As researcher at the Music & Computer Science Laboratory of Marseilles, he continued composing electro-acoustic music. His compositions have been played in festivals in France and Spain. His former work as a researcher and his previous articles published in France on the synthesis of Jazz harmony by computer constitute the foundation of ongoing dubbing challenges at Warner Bros.